Retimana Te Korou was convinced that having a town near his village would bring benefits to his people.

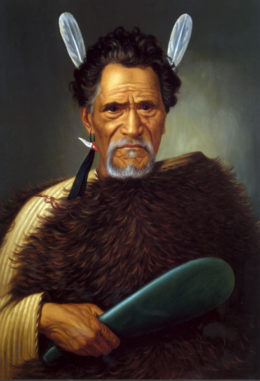

Retimana Te Korou, the principal Maori chief involved in the sale of the land for the township of Masterton, was born in the later years of the eighteenth century. He was the son of Te Raku and Te Kai from both Rangitane and Ngati Kahungunu peoples of Wairarapa.

Te Korou was among those whose life was severely disrupted following the displacements of peoples during the Musket Wars. Some Taranaki iwi who came to the Wellington area with Te Rauparaha, pushed their way eastwards, and some were living in Wairarapa. At first they lived alongside the Kahungunu and Rangitane iwi, but troubles eventually arose and a series of battles were fought between the two groups.

Some battles went well for the locals, but there were bad setbacks too, with some fights lost and warriors captured, including Te Korou. Te Wera of Ngati Mutunga was taking him to Wellington when he escaped by killing him. Realising it was no longer safe in Wairarapa, Te Korou, his wife Hine-whaka-aea, and their children joined other Wairarapa Maori at the stronghold of Nukutaurua, on Mahia Peninsular, where they remained until 1841.

Te Korou returned home, firstly as part of a group of Wairarapa chiefs that made peace with Taranaki Maori still living in Wellington, then on his family’s ancestral lands. When the missionary William Colenso called in to Kaikokirikiri pa, on the banks of the Waipoua River above what was to become Masterton, a Maori teacher had already converted Te Korou to Christianity. Te Korou’s family was all baptised and they adopted new names. Te Korou chose Retimana (Richmond); his wife became Hoana (Joan) and his surviving children Erihapeti (Elizabeth) and Karaitiana (Christian).

It was at the nearby Ngaumutawa kainga that members of the Small Farms Association met with Te Korou and his family and after consultation it was decided his son-in-law Ihaiah Whakamairu should return with the members, to start arrangements for the sale. Retimana did not sign the eventual deed, although he did sign to others around Masterton. His family’s names appear on the document however: Karaitiana, Erihapeti and Ihaiah.

By the 1860s Retimana seems to have ceded leadership of his hapu to his son Karaitiana and his son-in-law Ihaiah. Both father and son became supporters of the King movement in the turbulent years ahead, and Karaitiana spent some time away from Wairarapa, fighting on the west coast. In time Te Korou became reconciled with his pakeha neighbours, and on his death in 1882, many of Masterton’s leading settlers joined in the 300-strong cortege that made its way to his burial place, in the Masterton Cemetery.